The credit scores of millions more Americans are sinking to new lows.

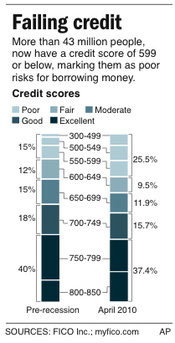

Figures provided by FICO Inc. show that 25.5 percent of consumers — nearly 43.4

million people — now have a credit score of 599 or below, marking them

as poor risks for lenders. It's unlikely they will be able to get credit

cards, auto loans or mortgages under the tighter lending standards

banks now use.

Because consumers relied so heavily on debt to fuel their spending in recent years, their restricted access to credit is

one reason for the slow economic recovery.

"I don't get paid for loan applications, I get paid for closings," said

Ritch Workman, a Melbourne, Fla., mortgage broker. "I have plenty of

business, but I'm struggling to stay open."

FICO's latest analysis is based on consumer credit reports as of April. Its

findings represent an increase of about 2.4 million people in the lowest

credit score categories in the past two years. Before the Great

Recession, scores on FICO's 300-to-850 scale weren't as volatile, said

Andrew Jennings, chief research officer for FICO in Minneapolis.

Historically, just 15 percent of the 170 million consumers with active

credit accounts, or 25.5 million people, fell below 599, according to

data posted on Myfico.com

More are likely to join their ranks. It can take several months before payment missteps

actually drive down a credit score. The Labor Department says about 26

million people are out of work or underemployed, and millions more face

foreclosure, which alone can chop 150 points off an individual's score.

Once the damage is done, it could be years before this group can restore

their scores, even if they had strong credit histories in the past.

On the positive side, the number of consumers who have a top score of 800

or above has increased in recent years. At least in part, this reflects

that more individuals have cut spending and paid down debt in response

to the recession. Their ranks now stand at 17.9 percent, which is

notably above the historical average of 13 percent, though down from

18.7 percent in April 2008 before the market meltdown.

There's also been a notable shift in the important range of people with

moderate credit, those with scores between 650 and 699. The new data

shows that this group comprised 11.9 percent of scores. This is down

only marginally from 12 percent in 2008, but reflects a drop of roughly

5.3 million people from its historical average of 15 percent.

This group is significant because it may feel the effects of lenders'

tighter credit standards the most, said FICO's Jennings. Consumers on

the lowest end of the scale are less likely to try to borrow. However,

people with mid-range scores that had been eligible for credit before

the meltdown are looking to buy homes or cars but finding it hard to

qualify for affordable loans.

Workman has seen this firsthand.

A customer with a score of 679 recently walked away from buying a house

because he could not get the best interest rate on a $100,000 mortgage.

Had his score been 680, the rate he was offered would have been a

half-percent lower. The difference was only about $31 per month, but

over a 30-year mortgage would have added up to more than $11,000.

"There was nothing derogatory on his credit report," Workman said of the

customer. He had, however, recently gotten an auto loan, which likely

lowered his score.

Studies have shown FICO scores are generally reliable predictions of consumer payment behavior, but Workman's

experience points to one drawback of credit scoring: the automated

underwriting programs lenders use can't always differentiate between two

people with the same score. Another consumer might have a 679 score

because of several late payments, which could indicate he or she is a

bigger repayment risk. But a computer program that depends just on score

won't consider those details.

On a broader scale, some of the spike in foreclosures came about because homeowners were financially

irresponsible, while others lost their jobs and could no longer pay

their mortgages. Yet both reasons for foreclosures have the same impact

on a borrower's FICO score.

In the past too much credit was handed out based on scores alone, without considering how much debt consumers

could pay back, said Edmund Tribue, a senior vice president in the

credit risk practice at MasterCard Advisors. Now the ability to repay

the debt is a critical part of the lending decision.

Workman still thinks credit scores alone play too big a role. "The pendulum has swung

too far," he said. "We absolutely swung way too far in the liberal

lending, but did we have to swing so far back the other way?"

Comments